It was standing room only at Lynchburg’s Court Street Baptist Church late on the evening of Oct. 16, 1878. The Iola, Kan., Register would later describe the crowd that gathered that night as an “immense throng,” reporting that while the church could seat about 2,000 people, “there were many more than that present.”

On that night, members of the black community in Lynchburg, Va., had convened at the church for a wedding ceremony and revival service. Some newspapers, including the Register, would identify the couple being married as Thomas Johnson and Malinda Bosher. Others would claim that Andrew Jackson Everett and Mary Rives stood at the altar that night.

What is certain, however, is that before the sun would rise the next morning, as many as 14 people would be dead and dozens more grievously wounded in what newspaper headlines across the country would call “The Lynchburg Calamity,” the “Fatal Panic” and “Terrible Disaster.”

Court Street Baptist Church was founded in 1843 as the African Baptist Church, a spin-off of Lynchburg’s First Baptist Church. The church building one sees today, at the corner of Court and Sixth streets, was built in 1879, a year after the tragedy.

It boasts the tallest steeple in Lynchburg — a steeple topped with a copper ball said to be more than 9 feet in circumference.

When the tragedy occurred, the church was meeting in a building located just west of the current structure. Newspaper reports of the day indicate that structure had seen better days. As the Lynchburg Virginian put it the day after the incident, “The church had been condemned and though repaired was believed to be unsafe, which doubtless increased the panic.”

News stories about exactly what happened on that fateful night vary, sometimes wildly. What appears to have happened, however, is that either during or shortly after the wedding ceremony a false alarm went out among the congregants that the church was collapsing.

Some newspapers describe the sound that prompted the alarm as breaking glass and place the blame on a pea-shooter in the hands of a mischievous boy. Others report that chunks of plaster fell from the ceiling, causing the massive crowd to panic and flee the building, trampling each other in the process.

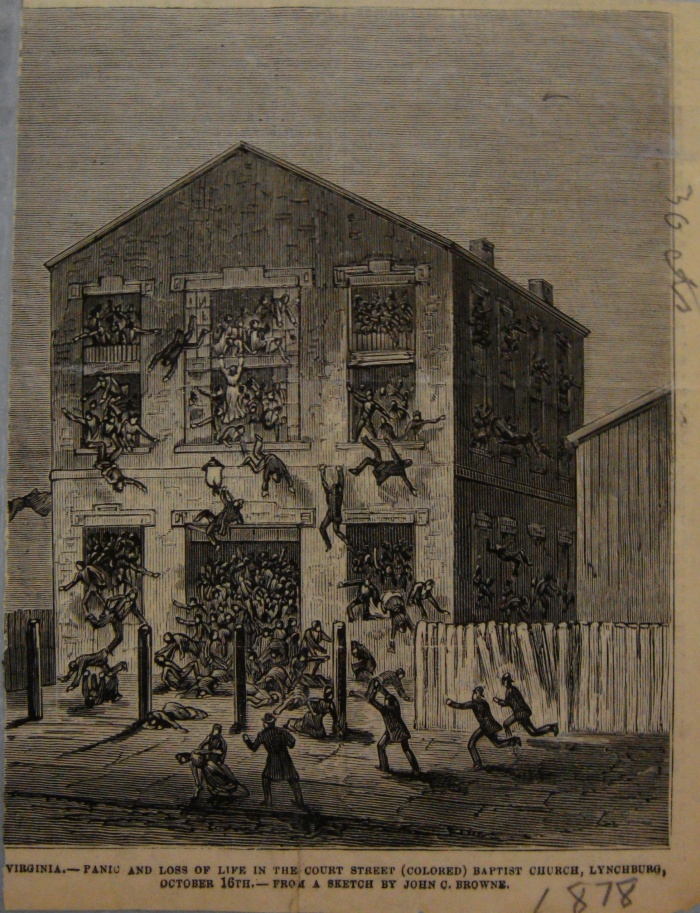

The Nov. 9, 1878, issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News reports it this way:

There was a general rush to the doors and windows. The audience-room being on the second floor, those who first reached the head of the stairs were so pressed on by the panic-stricken crowd that they were thrown down, and those who followed shared the same fate, until they were piled up almost to the head of the stairs.

Upon this mass of writhing humanity the throng that followed trod. Men and women rushed over it, careless of everything, so that they made their escape. The consequences were terrible. Many persons were either trampled or smothered to death, and more were badly wounded. Some who were near the bottom bore a weight which every moment threatened to crush their lives out.

Some newspapers also give harrowing accounts of victims leaping from second- and third-story windows to escape the building. The True Northerner newspaper in Paw Paw, Mich., published this account:

Many leaped from windows, and a few who were in the gallery jumped from the third-story windows. Three women who made that venture were killed outright.

Seventeen-year-old Maria Wilson was one woman who leaped to her death. An Oct. 18 story in the Lynchburg News, headlined “The Church Horror: Some Additional Particulars,” ponders Wilson’s final moments:

The view from the window through which Maria Wilson jumped to an instant death is simply fearful. Whether her neck was broken by concussion against the fence or pavement is not known, but certainly ninety-nine in a hundred would never know afterwards that they had attempted the leap.

Like everything else in this story, the number of fatalities reported in newspapers from New York to New Orleans and beyond varies, from eight to 14 people. The Orleans County Monitor, of Barton, Vt., reported that “14 people are known to have been trampled to death and 20 were so badly injured that a number cannot recover.”

The New York Herald, while admitting that “it is still impossible to get the full list,” reported on Oct. 18 that 11 were dead and 30-some wounded. It also provided a list of 19 of the wounded: Jane Lee, Lou Winfree, Judith Ward, Ellen Archer, Milly Leftwich, Paschal Horton, Miss Irvine, Lena Diamond, Henrietta Booker, Mrs. Jones, Eliza Ward, Martha Bopp, Ellen Shurr, Mary Smith, Mrs. Coleman, Caroline Irvine, Miss Watkins, Mary Ann Read and Walter Perkins.

Some newspapers even said the bride and groom died in the chaos that followed their blessed event. If that couple was Jack and Mary Everett — sometimes spelled “Averett” — they didn’t perish that night. Through at least 1910, the Everetts were very much alive and living on Floyd Street.

(As for Thomas Johnson and Melinda Bosher, I have yet to find any records of them or their marriage.)

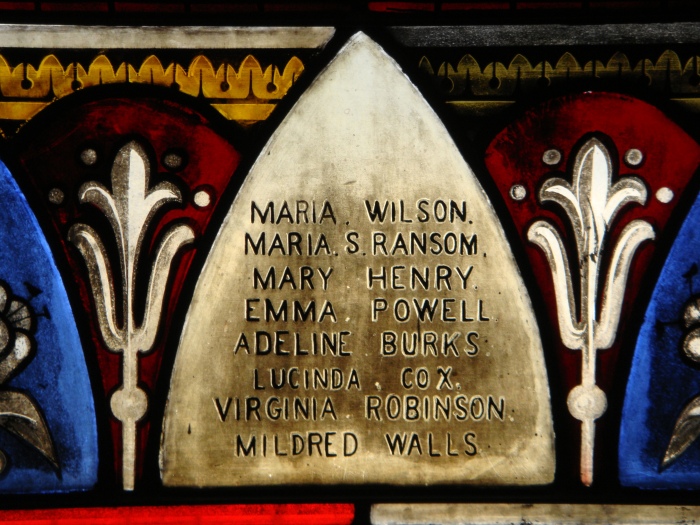

According to the Virginia Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics (records on microfilm at Jones Memorial Library), the following eight women died on Oct. 16, 1878, or succumbed to their injuries shortly after the tragedy:

Ann Cox, 16, born in Campbell County. Some sources call her Lucinda Cox or Arena Cox.

Mary Henry, a 60-year-old cook.

Emma Powell, 14 years old.

Virginia Robinson (sometimes Robertson), age 19.

Maria Ransom, 19 years old. According to the health department’s records, her mother’s first name was Malinda. The last name is illegible.

Millie Wood, a 26-year-old cook. She also can be found as Mildred Ward, Mollie Wood and Mildred Walls.

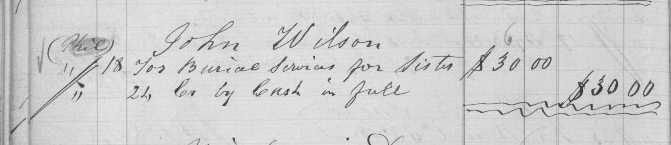

Maria Wilson, 17, a cook. She buried at Old City Cemetery in Lynchburg. Her brother, John, paid $30 for her burial.

Adeline Burks held on for 10 days after the tragedy, surrendering to her injuries on Oct. 26. She was about 50 years old, born in Appomattox, and her occupation in the records appears to be “housework.”

Next to each name listed was the cause of death: “stampede at church” or “church stampede.”

Also, I’m working on a bigger project involving this story, so if anyone has information — family stories or records, etc. — that they would like to share, please post in the comments section. Thanks!

So sad. Curious ,,, why would someone have so many names (especially 1st names)?

LikeLike

I don’t know. Maybe some were nicknames, maybe Ann was really Lucinda, kind of like Sallie can be Sarah and Mollie can be Mary, that kind of thing. Maybe it was like the “telephone game,” where by the time it went through a few people, it turned into something else. Hopefully, I’ll get it all straightened out at some point!

LikeLike

Great article, and did you find in the records any documented damage to the building or was it just crazy fear? I hope you’ll do more Lunchbag historical articles.

LikeLike

Other than some articles saying the building was in bad shape, no. They did tear it down after that, to build another church, so maybe it was in bad shape, or maybe just the tragedy happening there led to the new building. Still researching! Maybe I’ll find something else at some point!

LikeLike

Did you ever writd the follow up post?

LikeLike